Luke 10:25-37

Just then a lawyer stood up to test Jesus. "Teacher," he said, "what must I do to inherit eternal life?" He said to him, "What is written in the law? What do you read there?" He answered, "You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind; and your neighbor as yourself." And he said to him, "You have given the right answer; do this, and you will live."

But wanting to justify himself, he asked Jesus, "And who is my neighbor?" Jesus replied, "A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and fell into the hands of robbers, who stripped him, beat him, and went away, leaving him half dead. Now by chance a priest was going down that road; and when he saw him, he passed by on the other side. So likewise a Levite, when he came to the place and saw him, passed by on the other side. But a Samaritan while traveling came near him; and when he saw him, he was moved with pity. He went to him and bandaged his wounds, having poured oil and wine on them. Then he put him on his own animal, brought him to an inn, and took care of him. The next day he took out two denarii, gave them to the innkeeper, and said, `Take care of him; and when I come back, I will repay you whatever more you spend.' Which of these three, do you think, was a neighbor to the man who fell into the hands of the robbers?" He said, "The one who showed him mercy." Jesus said to him, "Go and do likewise."Good Samaritan, by Han Wezelaar, 1901-1984

I first learned about coffee hour questions when I was in seminary. Doctors at cocktail parties will sometimes find themselves buttonholed by a fellow guest asking for an immediate diagnosis, for say, a bad knee or ringing in their ears. Likewise, parishioners will ask clergy, during coffee hour after church, theological or church-related questions. Questions like: “What is the church’s position on abortion or divorce?” or “What is the unforgivable sin?” These are what's known in clerical circles as "coffee hour questions." In seminary, our professor of pastoral care reminded us that a more pressing personal and spiritual question often lay behind these impersonal “theoretical” questions. Our task was to listen for the deeper question and answer it. This is what happened when the rich young man ran up and knelt before Jesus and asked, “Good Teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?” (Mark 10:17-31) Jesus answered: “You lack one thing; go, sell what you own, and give the money to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; then come, follow me.” The rich young man’s question: “What must I do to inherit eternal life?” was a popular one. In today’s Gospel of Luke, a lawyer approaches Jesus and asks the same question: “What must I do to inherit eternal life?” The lawyer asked Jesus a question not for personal reasons but because he wanted to test Jesus. Perhaps he wanted to see if Jesus was orthodox enough? Or if Jesus knew the Torah. The question he asked was a good question. But Jesus, being a good teacher, turned the tables on the lawyer and answered him with a question to test him. “What does the Torah say? Jesus asked. The lawyer said, “Love the Lord your God with all your heart, mind, soul, and strength. And your neighbor as yourself.” Jesus replied, “You have given the right answer.” But Jesus, knowing that salvation depended on a lot more than having the answers to life, said, “Do this, and you will live." But the lawyer, who knew the devil is in the details, wanted to justify himself and asked: “And who is my neighbor?” As Barbara Brown Taylor writes in The Preaching Life: “But what he means is, ‘Who is not my neighbor? Whom may I legitimately set outside my concern and still feel good about myself?”1 So Jesus tells the story of the Good Samaritan. In this story, the “neighbor” is represented by two people—the man who was robbed and wounded on the road to Jericho and also the Samaritan passing by who helped the man lying on the side of the road. The despised Samaritan was the true neighbor, unlike the Jewish “religious professionals” who passed by the wounded man and did nothing.

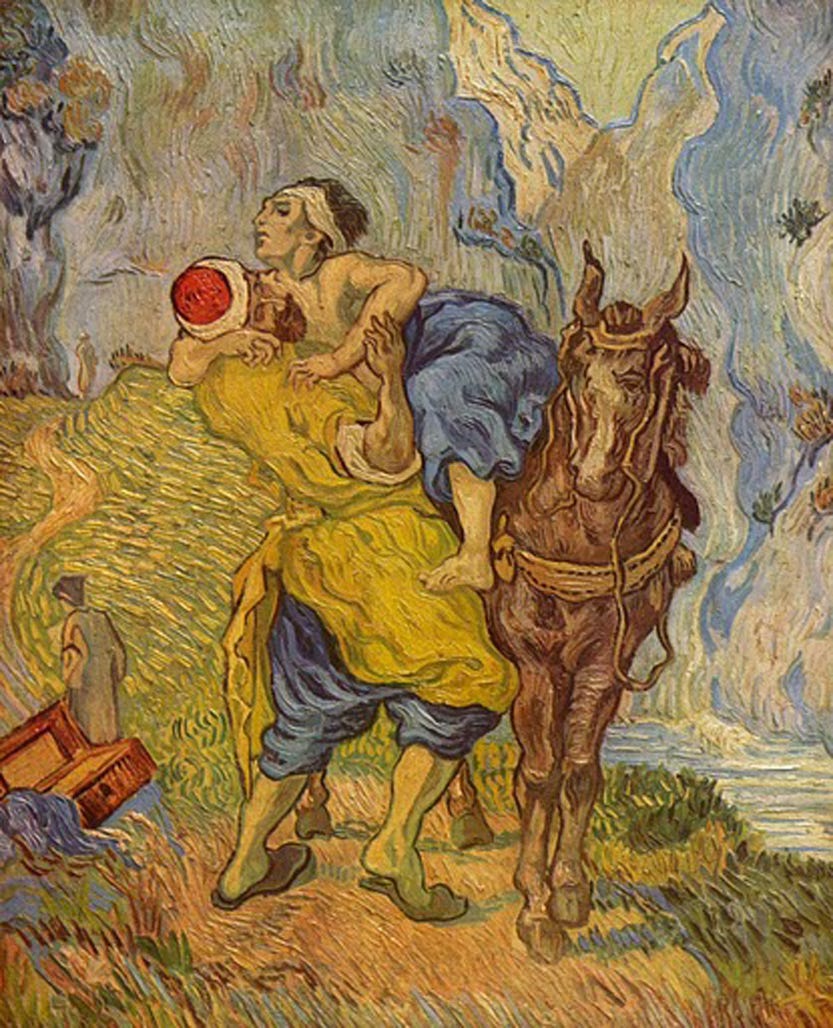

Good Samaritan, by Vincent van Gogh, 1890 Kröller-Müller Musuem

Martin Luther King, Jr., in his “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech said: The first question which the priest and the Levite asked was: "If I stop to help this man, what will happen to me?" But... the Good Samaritan reversed the question: "If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?"2

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. giving his last speech. Mason Temple in Memphis, Tennessee, April 3, 1968

When I was in 7th and 8th grades, each spring, everyone in my class was required to give a short speech and recite something before one hundred fifty students and faculty at our school assembly. One of the first poems I ever read that moved me was “Mending Wall” by Robert Frost. Frost writes about going out with his neighbor in the spring to survey and repair their joint boundary of stone wall. Frost starts the poem by saying: “Something there is that doesn't love a wall.” His neighbor’s only reply is: “Good fences make good neighbors.” Frost’s poem questions this:

“Why do they make good neighbors? Isn't it

Where there are cows? But here there are no cows.

Before I built a wall I'd ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,

And to whom I was like to give offense.

Something there is that doesn't love a wall,

That wants it down.”3

Over the past 60 years, as our global village has shrunk, being a neighbor is no longer defined simply by chance and geographic closeness. We are all interconnected. What the Trump administration does here in America to withhold USAID relief affects an orphan starving far in Africa or India. That orphan is my neighbor.

The Environmental group OceansAsia in Hong Kong found that discarded single-use face masks used to prevent the spread of COVID caused significant damage to the oceans. The face mask, which I used in 2020 and may yet use today, pollutes the sea and strangles seals swimming in the ocean tomorrow. That seal is my neighbor.

During the first Trump administration, President Trump promised to build thousands of miles of a “big, beautiful wall” on the US-Mexican border to keep illegal immigrants out of the United States. He built 452 miles of the wall, not paid for by Mexico but by us. While in office, he built only 80 miles of new wall. The remaining 372 miles consisted of replacing or reinforcing existing barriers. In January 2025, immediately upon taking office, President Trump resumed planning for 85 miles of a new border wall, and construction has already begun.

The question: Who is my neighbor? has never been more important. This is especially true since President Trump has started an unprecedented “Depression causing” trade war with our closest neighbors, Mexico and Canada. The Trump administration and the Republican Congress are also working hard to slash the ACA, Medicaid and Medicare, SNAP, Social Security, boost funding for deportations, and building internment camps. They have already defunded Head Start, the NIH and NEH, FEMA, EPA, several universities, housing assistance programs, public education and school lunches, PBS and NPR, and fired thousands of Federal workers. All of the people affected by these random acts of senseless cruelty are my neighbors.

Many years ago, a popular bumper sticker seen on cars in the San Francisco Bay area said: Practice Random Acts of Kindness. This phrase was coined in 1993 by a professor from Bakersfield College, named (ironically) Dr. Chuck Wall. Dr. Wall was looking for an assignment to give to his class on human relations in the business school when he heard a local radio announcer talk about yet another school shooting—“a random act of senseless violence.” That phrase—random act of senseless violence— intrigued him. He imagined turning the negative message into a positive one by changing just one word.

When Dr. Wall returned to the classroom the next day, he shared with his students their next project. He told them: “Go out and commit one random act of senseless kindness and write about your experience.”4

At the time, Dr. Wall had no idea what the efforts of his class would bring. He later said, "You would have thought we discovered human kindness—that no one had ever come up with the concept of being kind to another."

Dr. Wall defined kindness this way: “Kindness has four working parts: dignity, respect, compassion, and humility. If you have all of these things for yourself, then you will be able to share them with others. If we reach out with dignity, respect, compassion, and humility, we are likely to feel it being returned. It’s that simple and that hard.” Dr. Wall well knew the need for kindness because he went blind at the age of nineteen.5

Jesus’ story of the Good Samaritan epitomizes a random act of kindness. And the kicker was that it wasn’t a good Jew or even a “religious” person who did this kind act, but a Samaritan—basically, a 1st century outlaw.

Melanie Gruenwald, in her essay “Random Acts of Synchronicity”, encouraged her readers to practice "Synchronistic Acts of Kindness."6 She used a story reported in the L.A. Times to illustrate her point.

“Shortly before 5 p.m., Konrad and Jennifer Lightner were carrying their box-spring to the U-Haul when they noticed a cluster of children’s toys on the ground: a princess pillow, blankets and other plush toys. Three stories up, a boy and girl were sticking their heads out of the window, reaching their arms toward their toys. ‘Stay inside, go get your parents,’ the Lightners shouted up to them. That’s when the baby boy swung his leg over the windowsill.

“Jennifer Lightner, 29, immediately dialed 9-1-1 while Konrad Lightner, 30, threw the box-spring over the toys and jumped on. The boy’s fingertips were hanging from the windowsill, then from a cable cord, for about 40 seconds while Konrad Lightner prepared for the fall. ‘It was tense,’ Konrad Lightner said. But the boy landed perfectly in his arms. He added, ‘The parents are good parents—things just happen.’ Jennifer Lightner said, ‘It was so surreal—we were at the right place at the right time.’”7

Coincidentally, earlier that day, while the Lightners were moving their belongings out of their apartment, they got stuck in the elevator and they had to be rescued by the Fire Department. If their mattress removal hadn’t been delayed by the stuck elevator, they might have not been there to rescue the falling boy. The moral of the story—kindness begets kindness. And maybe even, nothing happens by accident.

The Lightners were strangers to this boy until they noticed the toys on the ground, looked up, saw the boy was in danger, and stood there as the toddler literally fell into Konrad’s arms. The question is not, “Who is my neighbor?” But what will you do for and with the neighbor that you meet? Who and wherever they are. Even if they are right in front of you. Even if they fell out of the sky into your arms.Photo by Dan Burton on Unsplash

Inspirational Quotes

Like the Good Samaritan, may we not be ashamed of touching the wounds of those who suffer, but try to heal them with concrete acts of love.—Pope Francis True compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar; it comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring.—Martin Luther King, Jr. "When I was young, I admired clever people. Now that I am old, I admire kind people."—Abraham Joshua Heschel

The Good Samaritan

by Mark R. Littleton8

“A certain Samaritan who was on a journey, came upon him and when he

saw him, he felt compassion… and bandaged his wounds.” Luke 10:33-34

Compassion.

The stoop of a listening father.

The touch and wink

of a passing nurse.

The gnarled fingers

of a grandmother

steadying a swing.

The clench of a surgeon’s teeth

as he begins his cut.

The open hand and pocketbook

of a traveling Samaritan.

The dew of heaven

on dry lips. Mending Wall

by Robert Frost9

(1874 –1963)

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it,

And spills the upper boulders in the sun;

And makes gaps even two can pass abreast.

The work of hunters is another thing:

I have come after them and made repair

Where they have left not one stone on a stone,

But they would have the rabbit out of hiding,

To please the yelping dogs. The gaps I mean,

No one has seen them made or heard them made,

But at spring mending-time we find them there.

I let my neighbor know beyond the hill;

And on a day we meet to walk the line

And set the wall between us once again.

We keep the wall between us as we go.

To each the boulders that have fallen to each.

And some are loaves and some so nearly balls

We have to use a spell to make them balance:

‘Stay where you are until our backs are turned!’

We wear our fingers rough with handling them.

Oh, just another kind of outdoor game,

One on a side. It comes to little more:

There where it is we do not need the wall:

He is all pine and I am apple orchard.

My apple trees will never get across

And eat the cones under his pines, I tell him.

He only says, ‘Good fences make good neighbors.’

Spring is the mischief in me, and I wonder

If I could put a notion in his head:

‘Why do they make good neighbors? Isn’t it

Where there are cows? But here there are no cows.

Before I built a wall I’d ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,

And to whom I was like to give offense.

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That wants it down.’ I could say ‘Elves’ to him,

But it’s not elves exactly, and I’d rather

He said it for himself. I see him there

Bringing a stone grasped firmly by the top

In each hand, like an old-stone savage armed.

He moves in darkness as it seems to me,

Not of woods only and the shade of trees.

He will not go behind his father’s saying,

And he likes having thought of it so well

He says again, ‘Good fences make good neighbors.’Photo by Moritz Mairinger on Unsplash

1 Barbara Brown Taylor, The Preaching Life, (Lanham, Maryland: Cowley Publishing/Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 1993) 124.

2 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, “I've Been To The Mountain Top” speech, April 3, 1968, Memphis, Tennessee.

3 Robert Frost, Come In and Other Poems, (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1943) 74.

4 Dr. Chuck Wall, Kindness: Changing our World (Bakersfield, CA: Kindness, Incorporated, 2011) 14.

5 Dr. Chuck Wall died at age 80 on June 8, 2021 in Bakersfield, CA.

6 Melanie Gruenwald, “Random Acts of Synchronicity”, The Kabbalah Experience, March 20, 2014.

7 Alene Tchekmedyian, “Burbank couple honored for saving toddler who fell out of third-story window”, LA Times, April 1, 2014.

8 The Widening Light: Poems of Incarnation, ed. Luci Shaw (Wheaton, IL: Harold Shaw Publishers, 1984) 72.

9 Robert Frost, Come In, Ibid. 74.

Truely, Good Samaritan work is un-clean and dangerous, costs you something, and is not merely a fleeting single moment but a caring, maybe even a burden, caried over time... yet we can all practice with our little deeds of kindness ... Hope you are safely back at home. Tim